Glossary term: Étoiles circumpolaires

Description: Dans la plupart des lieux sur la Terre, le pôle Nord céleste ou le pôle Sud céleste est visible dans le ciel à une certaine distance au-dessus de l'horizon. Pour un observateur situé dans un lieu spécifique, les étoiles semblent tourner autour du pôle céleste au fur et à mesure que le temps passe : chaque étoile trace un cercle dans le ciel, le cercle étant centré sur le pôle céleste vers lequel pointe l'axe de la Terre. Aux deux points où le cercle croise l'horizon de l'observateur, l'étoile en question se lève et se couche, respectivement. Pour les étoiles qui sont suffisamment proches du pôle céleste, l'ensemble du cercle tracé est au-dessus de l'horizon. Notre observateur ne voit jamais ces étoiles se lever ou se coucher. Ces étoiles qui ne se couchent jamais sont appelées étoiles circumpolaires.

Pour savoir si une étoile est circumpolaire, il faut prendre en compte la latitude géographique de l'observateur et la déclinaison de l'étoile - cette dernière étant l'angle entre la direction de l'étoile et celle de l'équateur céleste. Dans l'hémisphère nord, une étoile est circumpolaire si sa déclinaison est supérieure à 90° moins la latitude de l'observateur. Dans l'hémisphère sud, il faut tenir compte du fait que les latitudes sur Terre et les valeurs de la déclinaison ont toutes deux un signe négatif. En tenant compte de ces signes, dans l'hémisphère sud, une étoile est circumpolaire si sa déclinaison est inférieure à -90° moins la latitude de l'observateur.

Related Terms:

See this term in other languages

Term and definition status: The original definition of this term in English have been approved by a research astronomer and a teacher The translation of this term and its definition is still awaiting approval

The OAE Multilingual Glossary is a project of the IAU Office of Astronomy for Education (OAE) in collaboration with the IAU Office of Astronomy Outreach (OAO). The terms and definitions were chosen, written and reviewed by a collective effort from the OAE, the OAE Centers and Nodes, the OAE National Astronomy Education Coordinators (NAECs) and other volunteers. You can find a full list of credits here. All glossary terms and their definitions are released under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 license and should be credited to "IAU OAE".

Related Media

Stone Star Circles, Startrails above Stonehenge, by Till Credner, Germany

Credit: Till Credner/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Half day exposure to the north star, by Fabrizio Melandri, Italy

Credit: Fabrizio Melandri/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Dreamlike Starry Sky and Airglow

Credit: Likai Lin/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

La Grande Ourse aux quatre saisons

Credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Big Dipper and Comet Neowise C2020 F3

Credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Big Dipper Over the Mono Lake

Credit: Fabrizio Melandri/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Star Trails of the Forbidden City

Credit: Stephanie Ziyi Ye/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Related Activities

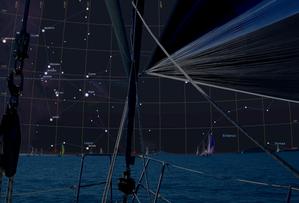

Navigation in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond

astroEDU educational activity (links to astroEDU website) Description: Learn the ancient skill of Celestial NavigationLicense: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) icons

Tags: History , Geography , Celestial navigation Age Ranges: 14-16 , 16-19 Education Level: Middle School , Secondary Areas of Learning: Discussion Groups , Modelling , Social Research Costs: Low Cost Duration: 1 hour 30 mins Group Size: Group Skills: Analysing and interpreting data , Asking questions , Communicating information , Developing and using models , Planning and carrying out investigations , Using mathematics and computational thinking