Glossary term: Osa Mayor

Description: La Osa Mayor es un conocido patrón estelar (o asterismo, para utilizar el término técnico) que forma parte de la constelación de la Osa Mayor en el cielo boreal. Consta de ocho estrellas: Alkaid, Mizar/Alcor, Alioth, Megrez, Phecda, Merak y Dubhe (Mizar/Alcor es una estrella doble). Las dos últimas estrellas del cuenco de la Osa Mayor pueden utilizarse para localizar la Estrella Polar (Polaris). El hecho de que las ocho estrellas tengan un brillo similar hace que la Osa Mayor sea especialmente notable (aunque Megrez y Alcor son ligeramente más débiles que las demás) y ha sido conocida con diversos nombres en muchas culturas. Las cinco estrellas centrales forman parte de un grupo de estrellas que se mueven juntas por el espacio (la Asociación Estelar de la Osa Mayor). Dubhe es rojiza; las otras siete estrellas son blancas.

Related Terms:

See this term in other languages

Term and definition status: The original definition of this term in English have been approved by a research astronomer and a teacher The translation of this term and its definition is still awaiting approval

The OAE Multilingual Glossary is a project of the IAU Office of Astronomy for Education (OAE) in collaboration with the IAU Office of Astronomy Outreach (OAO). The terms and definitions were chosen, written and reviewed by a collective effort from the OAE, the OAE Centers and Nodes, the OAE National Astronomy Education Coordinators (NAECs) and other volunteers. You can find a full list of credits here. All glossary terms and their definitions are released under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 license and should be credited to "IAU OAE".

If you notice a factual or translation error in this glossary term or definition then please get in touch.

Related Media

Constellations from the World

Credit: Stephanie Ye Ziyi/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Big Dipper

Credit: Arya Anthony/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Dreamlike Starry Sky and Airglow

Credit: Likai Lin/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Big Dipper in Four Seasons

Credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Big Dipper and Comet Neowise C2020 F3

Credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Related Diagrams

Mapa de la constelación de Virgo

Credit: Adaptado por la Oficina de Astronomía para la Educación de la UAI a partir del original de UAI/Sky & Telescope

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

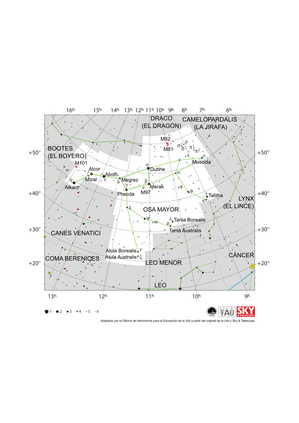

Mapa de la Constelación de la Osa Mayor

Credit: Adaptado por la Oficina de Astronomía para la Educación de la UAI a partir del original de UAI/Sky & Telescope

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Related Activities

Moving constellations

astroEDU educational activity (links to astroEDU website) Description: Let's learn how stars in constellations move through time using real astronomical images.

License: CC-BY-4.0 Creative Commons Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) icons

Tags:

Software

, Data analysis

, stellarium

, gaia

, hipparcos

, ursa major

Age Ranges:

10-12

, 12-14

, 14-16

, 16-19

, 19+

Education Level:

Middle School

, Secondary

Areas of Learning:

Guided-discovery learning

, Observation based

, Technology-based

Costs:

Free

Duration:

3 hours

Skills:

Analysing and interpreting data

, Asking questions

, Communicating information

, Developing and using models

, Engaging in argument from evidence